Issue №2: Trouble on the Grand Tour

by W.L. --

The following is a short story I wrote in 2018 that I'm moving over here because I find I'm still fond of it, and I didn't want to let it remain forgotten on a disused Medium account (and also because I needed something to test this site's new CMS). Read on to explore the hair-raising thrill-ride that is--or rather, will be--space probe racing!

"Trouble on the Grand Tour," by K. Lim (Staff Reporter). Originally published in Cool Sports! e-magazine, June 2173 issue.

Wandering Kuiper Belt Object -- New Horizons, 2017

Oort Objects Observation Station -- 19 Apr. 2173

"It's not supposed to be exciting," Jan Telluride says as she leads me to the observation deck. "Not on this end, at least. All the jockeying and bidding back on Earth, we don't even hear about it until hours later. By the time the centers of mass get here, it's all been locked in for quite some time."

She puts out an arm to hold me back as the door swings aside ahead of us.

"Don't go in there expecting the Kentucky Derby."

I nod, and walk out onto the deck of the Oort Objects Observation Station. About two dozen people are milling around an area that could comfortably accommodate two hundred. A few sit on lounge chairs pointed at a too-wide window looking onto the edge of the solar system, dots of color between a white floor and a black sky. More cluster loosely around a set of ad-hoc terminals, stepping over the cables that snake under floor tiles and behind wall panels. One stands against the window, leaning forward and scanning our corner of the heliopause.

She says her name is Iseult, a megascale-solutions-engineer with a robust online following.

"It's a pilgrimage for me. And it's good content."

She points out the New Horizons probe, or tries to -- I can't make it out at this distance until she lends me radio goggles.

"You'll be able to see it soon enough. We're set to be on a near-approach trajectory before the Cronus catches up."

I try to spot the Cronus with the radio goggles, but -- despite its size, speed, and EM noise -- I can't seem to find it.

"They send all sorts of streams back to Earth, sure. Visual, radiation, gravity -- but they're all boring. Send someone who knows what to look for, though..."

We spend some time talking about what she's hoping to capture during the fly-by as she records B-roll of the station, the onlookers, and the now-just-visible bodies of New Horizons and the Cronus. New Horizons, just a few months over 167 years old, is as ungainly a squat can of a probe as the day it was launched, covered in antennae, sensor booms, and protective foil only lightly pocked by extraterrestrial dust. It is now 158 years since it visited Pluto, 155 since Arrokoth, and 133 since it passed out of the heliopause and into interstellar space. Cronus is a relative newborn, spending the past three months as a sleek gray bullet at 0.03c before slowing to match its grandfather's pace. Everything moves so smoothly and gradually you could convince yourself we were all simply adrift and not hurtling out of the solar system at 85 thousand miles per hour, spectating an inconceivable high-speed chase. The complex slingshot maneuver the Cronus was set to perform when it passed the old probe, Iseult tells me, would smash that illusion.

Saborsen, a sociology graduate student, agrees.

"That's the moment that gets clipped and endlessly replayed from every angle -- the moment when all the hours of labor, thought, and belief are made visible."

She tells me she is studying the probes as a locus of human myth-making.

"There's something a bit like magic in it -- a certain concept of humanity produces the probe, and changing the physical context of the probe changes that concept."

I am admitting her logic has lost me when Station Astronomer Chen walks over, star chart in hand, and makes his introductions. Our conversation diverts to a broader survey of the objects in this portion of the cloud, including a few manufactured ones. Over the next twenty minutes, a crowd gathers around us.

"And there, by 2412-Alvarez, you can see a very early installation -- one of the first this far out. A joint NASA-ESA venture. Looking at the map again..."

He traces a curve on the star chart, now unrolled along the floor. The crowd bows to get a close look.

Iseult points a finger at the window. "Whose is that one?"

As we turn our heads, the Cronus is shattering into thousands of pieces, each glittering in the station's beams as they spin away from their intended course, tumbling end over end into the darkness -- and out of the middle of them speeds the core of something heavy, ungainly, and fast.

Cameras are already out and focused on the spreading cloud of debris; save for Saborsen's, which is trained on the crowd, and for Iseult's, which she has dropped on the ground and is now scrabbling after. By the bank of screens, a group of technicians huddles as they sort through a pile of possible trajectories. One slips away -- conspicuously trying to appear inconspicuous -- into a room marked "Emergency Control Access". The room buzzes, then hushes as a foot-long shard of iron stabs into the window.

It's not supposed to be exciting.

--

Voyager 1 Radio Signal Image, 2013

--

Costa Aerospace Materials Remediation -- 19 Oct. 2172

Like many who worked on the first generation of orbiters, Paulo Las Cases has a persistent cough. His accompanies speech and not, thankfully, exertion -- trawling the immense Costa junkyard requires much more of the latter than the former. Not none at all, though.

"Every racer has his man in the junkyard. Sometimes, that means fights. It's better when they're with words -- the infections you get in a rocket graveyard are nasty."

Las Cases gestures to a canopy that will shade us from the midday Brazilian sun. As my eyes adjust to the relative dark, he picks up a canning jar filled with stubby gray rods.

"Just last week, Emilia -- she's Petersen's hand out here -- pulled a gun on me for this! Do you believe that? A man nearly dead over lithium!"

He hands the jar to me.

"Of course, God knows how many died getting it out of the ground in the first place. Add one last name to the list before it gets shot off into space, to trouble mankind no more." He puts a kerchief to his mouth and coughs. "I'll be glad to have it off my hands."

Handing the jar back, I ask if he can support himself and his children in this line of work.

"It is" -- he pauses -- "Inconstant. We are always running out of whatever they ask for, then their scientists huddle and decide what the new best way to make rockets go fast is. Sometimes that includes us, sometimes not. I'm lucky -- I have worked here for thirty years now, ever since Low Earth went under -- so if the junkyard has anything like what they want, I know. If I'm very lucky, I know where, too."

The loading door of a cargo trailer is open just outside the canopy. Las Cases puts the jar into some plastic packing material and slides it onto the bed of the trailer.

"When I was younger, Golding would offer to put me in on the real money -- a construction job. But no."

He looks me in the eye.

"Space had nothing for me."

--

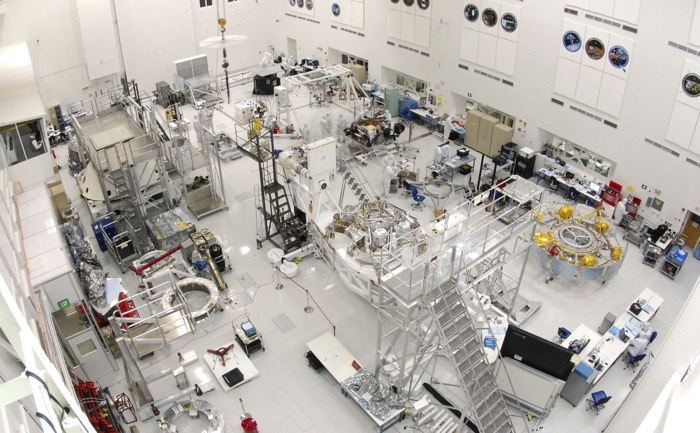

JPL -- 1 Nov. 2172

After spending an extra half-hour in the decontamination room -- the attendant tells me a mis-installed filter triggered the particulate detector -- I scrunch-scrunch-scrunch into the research facility and am greeted by Doctor Jackson and her team, similarly clean-suited-up. One of the other engineers hands me a folder, which I flip through while they usher me into one of the Jet Propulsion Laboratory's silo-sized freight elevators. In the flaps, sheaves of conference proceedings and abstracts hide behind full-color cut-away diagrams printed on heavy card stock.

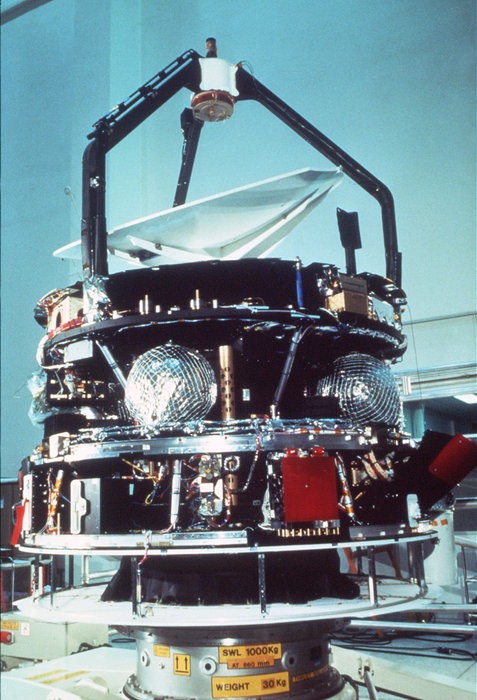

We stop to let on a sharply-twisted metal donut about three feet across, carried by two attendants and trailed by a third holding the ribbon of cables that sprout from one of its joints. They will be heading to the same stop as us -- Doctor Jackson introduces me to the core of the magnetic pulsion system, which promises to accelerate the center of mass through clever manipulation of the sun's magnetosphere.

"And when we get to Jupiter, oh wow. That will be something."

The third attendant gestures to the cables they're holding, pointing with a white plasticated finger to the various conduits electricity will soon course through, turning the charge of the solar wind into magnetic gription.

A recorded voice tells us that we've reached floor L3, the Mass Acceleration Studies Hangar. The door slides to the side, revealing a fifty-foot tower of smooth dull gray, topped with an explosion of dishes, antennae, and rainbow wires. A fleet of ladders have rolled up beside it, jockeying for space with lifts carrying up power cables and pressure lines, and with instrument boxes hanging from ceiling tethers. I imagine I too can feel the gravity of it, the tug of its mass, and finally appreciate why Doctor Jackson is so pleased.

"Even with the advantages of orbital launch, we were reaching the physical limits on the speed to which a gravitationally-significant mass could be accelerated with liquid-fuel rockets." Jackson beams. "We found a way to get new limits."

One lift comes over for the pulsion core and its attendants, a second for Jackson and me. She trusts all the engineers working under her, but still needs to oversee critical points like this.

I ask how she finds working for Golding.

"It's a great commission to work on, very exciting -- very challenging in a way very little of our other work is. Not that our other contracts are unimportant, of course. No, no! The aerospace industry needs people as capable of delicate work as those of us at JPL. But those are solved problems. These" -- Jackson sweeps her arm over the iron hulk of the Cronus below -- "Still need solving!"

A white-gloved thumbs-up from one of the attendants. Doctor Jackson gets on the radio to request the technicians begin cycling through power-on tests -- she looks over at them, sequestered behind a glass window a short distance above our heads.

"A little verbal gaffe there, I suppose. You would think that with the number of reporters I've been talking to lately, I'd have this down to a science."

Another thumbs-up and we begin to descend. The thrum of a decompressor fills the silence.

"In a way, it's continuity. We're bringing a form of new life to missions from the days of NASA, extending JPL's role in a way they never could have imagined."

She opens the gate on the lift and gestures for me to step off first.

"With this, New Horizons definitely gets the lead on Pioneer 10 again -- and I think she manages to catch up with Voyager 1."

--

Curiosity at JPL Spacecraft Assembly Facility, 2011

--

Gold Plate Station II -- 29 Nov. 2172

Ostensibly, the gold leaf covering the broad disc of the station serves to shield the interior from charged particles in the solar wind. Amy Wisła disagrees.

"People call him a genius, but all he's really good at is branding. We have to shut down for a week every year to patch the stuff 'cause he won't let us cover it."

We clip onto a guard rail on the bottom of Gold Plate Station II, illuminated by the Earth above us and its reflection at our feet. The burnished gold is filled with the distorted image of an immense storm forming in the equatorial Atlantic.

"This is getting to be a bad orbit for space junk, and all the gold dust isn't helping."

Does that make working out here dangerous?

"Mostly no. Right now, we're angled so the main worksite is leeward" -- she points at the edge of the station slightly closer to the Earth -- "So we miss the worst of it. When the deadlines start to slip and we're working everywhere at once, though..."

She shows me a heavy brown patch on the left leg of her suit.

"A one-millimeter sliver went through at orbital velocity. Pow! Stung so hard it knocked me the hell out. They had to get the nurse practitioner over from Station I to bring me around. There were no complications, though, so I was back to work the next day." She notices that I have stopped moving along the guard rail. "Don't act so shocked -- it's not like you need legs up here."

Wisła laughs, the volume peaking our helmet radios as she deftly moves hand-over-hand along the rail towards the skeleton of the new Jackson-model Cronus.

"Anyway, what's the point of being up in space if you aren't out in space?"

Behind her gold-tinted visor, the humor drops out of her face.

"They know the kind of people who work up here think like that, of course. It's why I wouldn't have gotten paid if I didn't show up to shift the next day -- they say the life support is part of my compensation package. That I've paid off the ride up but still need to earn the ride down."

She unhitches our tethers from the radial guard rail and hitches them onto the construction platform.

"So you can see we've got the basic framework in place -- that's all set 'cause the design is finalized. Plus we've got some work done on the larger antenna array for the magnet thing, though we're going to have to wait for them to send us one of the JPL folks to install the core of it. Mostly it's the weight, though. We need mass, density, heft to tug on the probes; that'll be a couple months of deliveries from Earth and the mining ops and whatever large junk we can catch. And all this just for a stupid rich-guy race."

Her gloved hands grab the bar circling the platform. She leans inward.

"The Tour was, like, what got me into -- interested in space. Like we were finally picking up where we left off, challenging each other to be greater than the Earth can hold, like all those myths about half-gods and constellations. Instead, we're throwing billion-dollar rocks at them."

We spend another hour looking over the Cronus. Wisła describes the work that will need to be completed before Golding does his on-site inspection a month from now -- sooner than she'd like. Heading back to the airlock, I thank her for her help.

"Yeah, well, I'm happy to take a break on company time. Give my best to Golding for sending you on this press junket."

I ask if she's worried about reprisals from Golding for expressing that attitude.

"Eh, he doesn't care about that. One of the few advantages of working for him over the rest."

Wisła's helmet tips up towards the Earth.

"Too few."

--

Okeechobee, FL -- 21 Dec. 2172

Golding cannot make the planned inspection, so I instead visit him at his home overlooking Okeechobee Bay. I say home -- he doesn't.

"When you take an interest in the race like mine, you've got to be near the action," he tells me as we sit in his wood-paneled study, drinking small glasses of a 2018 Napa Valley wine. "There's only so much mass you can send into space, only so much delta-v that the world can give you, no matter how much cash you have on hand -- so you've got to be smart, you've got to be fast, and you've got to know people."

The Minnesota native only used to visit the Cape for launches, when the jockeying was less intense, less precise. He shows me pages from a sequence of meticulous daybooks -- two-day hotel visits become two-week hotel stays; P.O. boxes become addresses; rentals become mortgages become title deeds. Alongside records of handshake deals and iron prices, I notice speaking engagements, media interviews, ad purchases, editors-in-chief.

"I didn't know it was my calling, I just fell into it -- that's the definition of a calling."

He swirls his wine, looking out into the dark storm massed over the ocean. I can see white foam in the choppy water.

"You know, I'm not the only one with a calling. If there's a mistake I've made, it's letting them hide behind me, hide in their work. It's those fearless people on my team, leading through action and example, who deserve attention. Who could make a connection with every dreamer out there."

He grins, selling me something.

"If it keeps up like this, you'll miss your flight."

Heavy rain hits the window facing the ocean, sliding down in thick rivulets behind a faint image of Golding smiling hyena-wide, thrusting a wad of betting slips into the air -- the day New Horizons finally overtook Pioneer 11.

--

Cometary Express -- 18 Jan. 2173

It is possible to spend forty years with the European Space Agency without spending a single day in space -- or so Enrico Grimaldi tells me over a lunch of pâté and crackers.

"I never felt the spark to do it until I finally retired three years ago. I was in Consistency, you see -- safely ensconced from the wonder of space travel behind reams of regulations in need of reconciling. The binders! Someone your age, you haven't seen as many binders in your life as we filled each week."

A waiter swims by above us, outside the reach of the dining area's artificial gravity. They are above the line where carpet, tapestry, and oak panelling abruptly give way to pocked gunmetal-gray. A silver filigree runs through their apron -- embroidered "CE" in the lower-right corner -- and shines dimly pink in the light of a rapidly receding Mars. Their pants are light, wrinkly, medical-blue, and bulk-purchased.

"Frankly, it was usually the opposite. Anti-spark, a burst of positrons. Imagine being at my desk when the letter comes in, asking, in as many words, 'Can we play billiards with your probes? Also, nota bene, we did already do it."

He swallows a mouthful of the champagne before continuing.

"And the debates were endless! They'd been end-of-lived, sure, but they hadn't stopped being multi-billion-dollar pieces of government property. Even then there was so much affection for those old wanderers. And of course we're on the phone with NASA, all watching in horror as the American congress votes to deed over their probes to the Tour, with Golding and Petersen and Teller and Maria grinning and clapping at the dais. And we get so stymied it's all we can do to go, 'Do all the gravity assists and slingshots you want, just don't touch the damn probes!'"

Agitated, he leans back and runs a hand through absent hair. He breathes in slowly, then out quickly in a half-snort.

"I guess it was all a bit futile. It's not like we could have enforced a 'no,' anyway. Never built any battle-cruisers or gauss-rifled dreadnoughts. We found peace in the stars -- at last!" Another mouthful swallowed. "My husband calls it a 'potemkin peace' -- why bother having a war in space when you can have one on Earth? There's barely anyone to kill up there, and so long as the fighting doesn't get out of the atmosphere, well, it can't really be a war, can it? Just a regional conflict, happening nowhere else in an infinite expanse, not worth raising a fuss over." A sip of wine. "Bit of a firebrand, that one. But it's true -- ever since Apollo-Soyuz, no-one has objected to doing a bit of space science with one hand while funding a proxy war with the other."

He checks a screen on his wrist and smiles.

"Always been this way, I guess! You man your post until someone shows the rules never applied to them anyway. At least I got Petersen to pay up when he sheared Giotto's aerial off. They can be made to obey the rules of their own game, if just barely."

Grimaldi begins looking up, scanning the space outside of the dining area.

"After the third time they pushed back my retirement, I prom -- ah, here he comes."

A man with a billow of gently flowing gray hair drifts down from the gunmetal and lands smoothly at Grimaldi's side. They embrace before Grimaldi turns back to me.

"If you'll excuse it, I really ought to get back to the wonder of space travel -- I did promise."

The pair walk out of the dining area and back into the gunmetal, their last step a little leap into microgravity. I have another cracker.

--

--

Cometary Express -- 2 Mar. 2173

I am charged two days fare to receive the following message:

"The Committee thanks you for requesting our comments on your Grand Tour story. We have only one: Please reconsider. The Grand Tour organizers -- and Golding in particular -- have debased a legacy of selfless inquiry and exploration conducted for the benefit of humankind in toto in pursuit of personal glory and triumph. Until all Grand Tour organizers follow the model of Jer Terrel -- manufacturing and launching new centers-of-mass to return the probes to their original trajectories, and further re-establishing their radio contact with Earth -- contact OPATS is willing to pay for -- the committee can approve no coverage of the Grand Tour.

As you are already in transit to the edge of the solar system, we have taken the liberty of attaching a list of out-system historic space science sites -- some still in operation -- more deserving of press and attention.

With respect and hope,

Outreach Committee, Our Past Among The Stars"

--

Oort Objects Observation Station -- 19 Apr. 2173

As panic scatters the crowd Saborsen alone is moving methodically, retrieving nondescript containers from inside closets and behind panels. She pushes a large box into my arms -- its loose contents clattering with the impact -- and says she'll tell me what she knows if I help her bring these to her shuttle.

"They're not bombs or anything like that. Just storage drives. Trajectories."

We race down corridors to the lower docking bay. Her name, I learn, is not Saborsen. She is not a graduate student. She did not fire the mysterious rocket at the Jackson-Golding Cronus -- that was a different team in her organization. To pull it off again, they'll need to know exactly where each probe in the Tour is -- information that Oort Station has been closely tracking.

The airlock slides open and "Mata" waves us inside, urgency in their movements. "Saborsen" shoves her cases into a corner and races over to the command console, pounding in a set of codes. Mata seals the airlock behind us and starts throwing levers all around it -- releasing the docking mechanism.

Suddenly aware of how small the shuttle is, I drop my case next to Saborsen's and sit heavily on the unibody bench. The weight slowly lifts as we pull away from the Station. Sighing, I buckle myself in.

Are they with Our Past Among The Stars?

"OPATS?" Mata scoffs as they begin securing the containers to the floor. "No. We're not the homeowner's association. We're here to fight."

Saborsen glances back from the console. "To start a sort of war, in fact."

Mata nods. "Every time one of those monsters tries to climb out of Earth with a pile of bodies beneath them, we're going to shove them right back down. Every massive finger they reach out to pull down the sky, we'll snap it just like this one. That's the mission of the Pause."

The console pings, its course logged in. Saborsen pulls a storage drive out of the box before Mata belts the rest of them down. She then buckles herself into the seat across from mine. "On the model of magnetopause, heliopause. A defined outer limit to a body's power or influence."

"And it will be," Mata continues, "Until they leave their stolen toys, stop acting like children playing with their parents' tools, and help to build something good back on Earth."

What if they want to fight a war? What if the game of the Tour only ever offered an approximation of the challenge -- the power -- they really wanted?

Mata crosses their arms and shrugs. "Then we'll fight."

Saborsen says nothing. She grips the drive tighter, fingertips angling back.

I look out through the glass. The sun is small, white, and far away.

• CS!