Issue №1: Spring Melt

by W.L.

——

In teaching others math you necessarily learn the art of pulling problems out of solutions—any time you find a triangle in the built world, there was at one time the problem of fitting the triangle to the work.

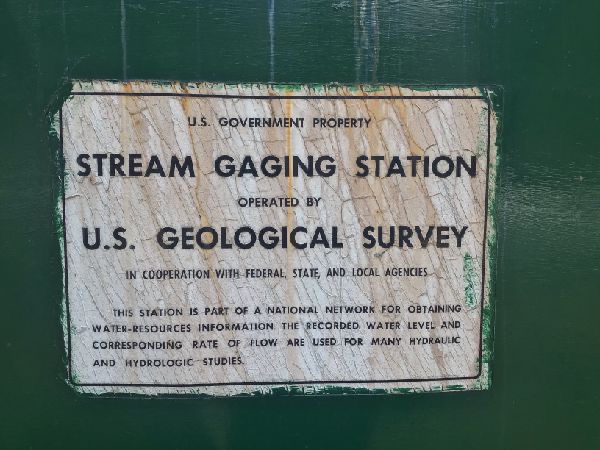

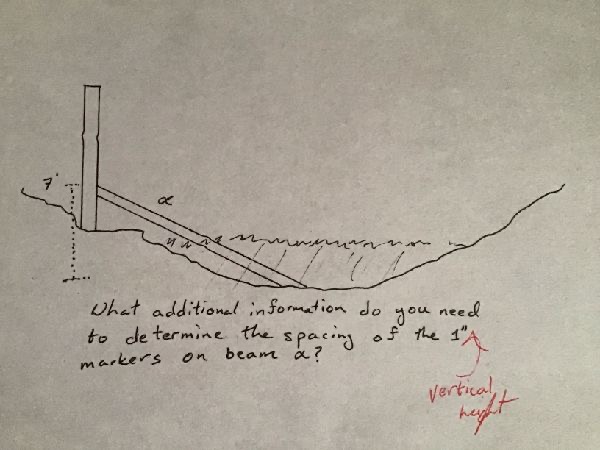

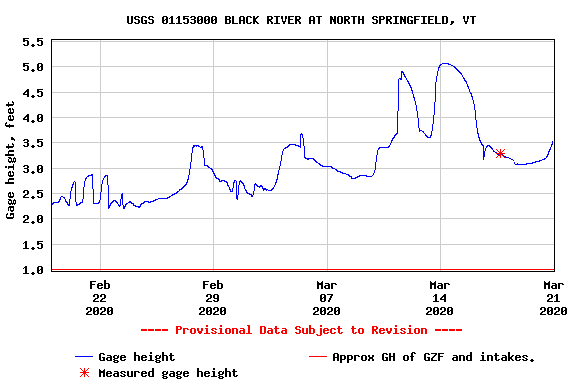

Some typically quiet part of your brain then rouses and insists on asking, “How did the USGS work out the markings on that slanted measuring bar that connects the bottom of the streambed with the vertical measure on the shore?” And it begins to sketch out diagrams, laying alternate pathways, axes to leave labeled or conspicuously unlabeled, questions that should prompt the student to ask for the right information and show the right work.

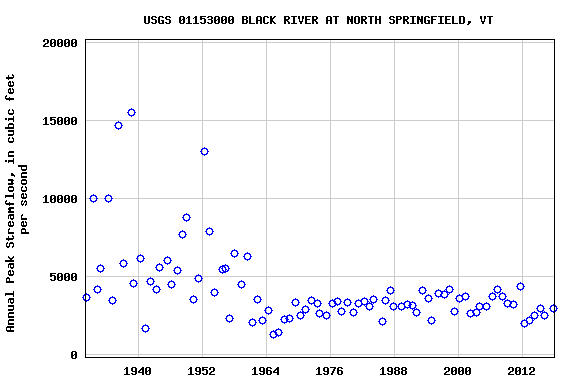

All of which obscures the greater question—why should the USGS be maintaining a measurement station, simple as it is, on a minor tributary of the Connecticut River? Standing beside the Black River today, one could hardly imagine that the river used to routinely leap its banks and flood the downstream towns—a problem addressed by the building of the contentious North Springfield Army Corps flood control dam in the 1950s.

Right now, though, the dam looks almost preposterous—a hundred-foot-tall embankment of earth and concrete built to control what is scarcely more than a stream. Like all Vermont rivers, the dangers of the Black river rise during the snowmelt—and this year provided little snow for the purpose.

Even in a diminished year the spring water still does its work. The falls in town shoot water downriver with a strength that will fade as summer nears—enough power to make clear, for example, the usually invisible mechanism that meanders our rivers. Sitting on the stonework of the old waterside mills, you can see the thin band of faster, more turbulent white water traveling a sinuous path that curves towards the outer bank, sanding away thin layers of bedrock schist.

I suspect that many of the small islands that dot the Black River are remnants of of meanders that grew too sharp to hold the main body of the river and have since faded to the calm shallows that cut these bars of sand, silt, and soil off from the shore.

It’s a lean year for the Connecticut River too, but I can scarcely tell—too much time walking its tributaries has lowered my expectations. Crossing the railroad bridge across one of the Connecticut’s series of rapid drops through Bellows Falls, I was more unnerved by the billowing mist spraying through the beams and the attendant stiff, unpredictable gusts of displaced air than I was by standing forty feet above the water on a houndstooth-metal walkway less than a meter wide.

Heights have been the peak of fear to me since I was young child avoiding the windows of the observation deck of the Corning Tower. It’s been something of a hobbyhorse for my subconscious—routinely confronting me in dreams with unrailed stairs to climb and wide chasms to jump. Yet working in a mountaintop tower for a season seems to have done what thousands of hours of dream-simulations could not, finally convincing me deeper than reasoning could that simple potential energy was not in of itself a thing to be feared. Small amounts of energy, after all, can keep an unstable equilibrium in balance—it’s when things begin to move that things get dangerous. The moving river takes that instability and does what the physicists call Work.

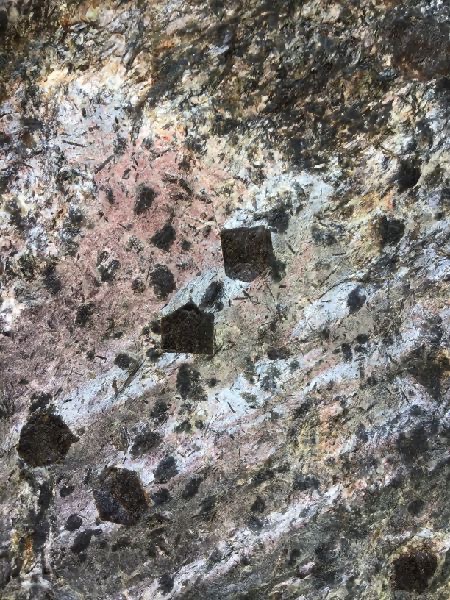

This newfound security with heights is not quite so strong, though, that it can convince me to cross another railroad bridge, one with no continuous walkway besides the rails themselves. Instead, I climbed down into the ravine it crossed. The water had been doing its sanding work here as well, carving meter-wide potholes into the mica-rich schist. Near the river, the rock had been worn into smooth belts that belied their interior structure of thin layers and flakes. Three meters or so above the river, however, things looked quite different—probably exposed by fracturing as the river wore its supports away, the rock face shone in complex, rough patterns following the underlying contours of the schist and dotted by black crystals that jutted out from the stone: Garnets.

It’s this jutting behavior that gives them their name—tough enough to resist weathering better then the surrounding rock, but not tough enough to resist rounding into little protruding hemispheres, the Greeks compared them to pomegranete seeds—with, in the best of cases, their exceptional red-purple color. It takes a relatively fresh exposure to see their sharp crystalline structure that is typically appears in section as irregular pentagons, and to see that these garnets have little color.

I was able to work one crystal free, exposing its 3-dimensional structure—approximately a dodecahedron—the curious order that a river far slower and more deep can work.

——

Every river I’ve talked about here is dotted with hydropower plants—a product of their natural falls. Most reading this have probably previous seen that hydropower sees less mortality per kilowatt-hour than most baseline power sources (excepting, curiously, nuclear). And yet—not zero. Even when neither physics, chemistry, nor biology demand injury, money still does. From Muriel Rukeyser’s “The Book of the Dead,” on the Hawk’s Nest Ridge disaster:

How many feet of whirlpools?

What is a year in terms of falling water?

Cylinders; kilowatts; capacities.

Continuity: Σ Q = 0

Equations for falling water. The streaming motion. The balance-sheet of energy that flows

passing along its infinite barrier.

It breaks the hills, cracking the riches wide, runs through electric wires;

it comes, warning the night,

running among these rigid hills, a single force to waken our eyes.

They poured the concrete and the columns stood,

laid bare the bedrock, set the cells of steel,

a dam for monument was what they hammered home. Blasted, and stocks went up;

insured the base,

and limousines

wrote their own graphs upon

roadbed and lifeline.

The poem is excerpted at https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/92725/the-book-of-the-dead-the-dam but I recommend reading the full poem in U.S. 1 or in Rukeyser’s collected works.

——

The stream stops.

What We’re Missing in Sports’ Absence by Joe Bush

https://joebush.net/2020/03/17/what-were-missing-in-sports-absence/

“Last night, when I heard Dick Vitale practically scream that the noise in the Fieldhouse that night was the loudest he’d ever heard, I cried. That noise, not just in the Fieldhouse but at any mass sporting event, is special. It’s spontaneous and it’s unreplicable, only produced by a mass of people in joined elation. That noise is felt more than it can be heard. That night, that noise from the bleachers above me made me recognize that the game on the floor beneath me was special.”

——

The melt is nearly done, but things aren’t green yet.

——