Issue №10: Other Waters

by W.L.

“Their appearance was exactly that of the sea in a storm, except as to color, not the least sign of vegetation existing thereon.” — Impressions of the Great Sand Dunes in what would later be named Colorado, recorded by General Zebulon Pike during his expedition into the Southwest, 1807.

While the details are a subject of ongoing debate, here is the rough sequence of events: Around thirty million years ago, following the massive, millions-of-years long Laramide tectonic subduction event that built up the Rocky Mountains, a rift tore apart the bedrock extending past the Southern Rockies, building a volcanic mountain range to the west (the San Juans) and a twisted-bedrock range to the east (the Sangre de Cristos) of what we now call the Rio Grande valley. The Grande, however, would take millions of years to develop into the river it is today—the early valley was instead dominated by vast lakes, often isolated from any drainage to the ocean. While the river eventually incorporated and drained many of these lakes, a few remained in isolated basins. The northernmost of these, ancient “Lake Alamosa,” formed in the crook where the San Juans and Sangre de Cristos meet, was fed only by the water coming down from the two ranges, like the stream that carved out the Mosca Pass.

Around 100,000 years ago, that flow ceased to be enough to maintain a lake of approximately 4,000 sq. km. (1500 sq. mi.) in area, and it reduced to something like its present state—a vast sandy plain, dotted on its western side with meandering streams and shallow swamps.

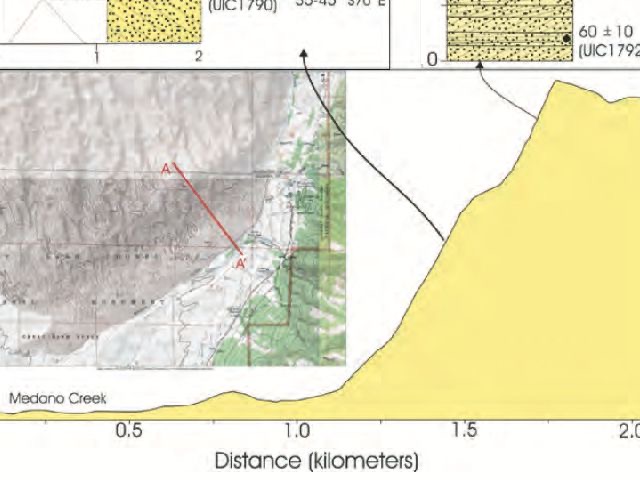

From the USGS publication Geologic Map of the Great Sand Dunes Park.

In the Northern Hemisphere, winds tend to blow from west to east. When a sandy lake like Alamosa dries up, one generally expects those westerlies to slowly blow the sand eastward until that sand fills in some valley or runs up against a mountain, where it stays until the Earth’s natural processes turn it into soil or sandstone or wash it down to the sea. Yet before the sands of former Lake Alamosa can reach the Sangre de Cristos, they find that the streams that once fed the lake still flow, and even these reduced creeks can drain wind-blown sand back the swamps in the west of the basin, kept steady by the slow melt of the ice and snow atop Mount Blanca. And so a great mass of sand stays in equilibrium, piling in dunes at the creeks’ edge—the 80 square kilometer (30 square mile) expanse of the Great Sand Dunes.

Some sand of course is carried past the creeks—as can be seen here—note the sand punching its way up a glacial U-shaped valley.

The dunes’ crests, large and small, are often marked by thin, arcing bands of black sand a few millimeters thick. While the wind over the Great Sand Dunes generally flows from the west, occasional strong easterlies sometimes storm down the side of the Sangre de Cristos, capable of moving the coarser grains that characterize the Dunes’ eastern flank—as well as denser sands, containing magnetite and garnet, that erode from those mountains. These the easterlies carry up to the peaks of the dunes, along with a a great quantity of other sand. That other, lighter sand, however, can be moved by the basin-weakened westerlies even as it fails to shift the magnetite—a natural magnetite-panning operation that has been running for 100,000 years.

A sample of normal sand from the dunes, with what I believe to be some pink feldspar carried down from the granite of the Sangre de Cristos.

A sample of magnetite sand—note the proliferation of angular black grains among the quartz and other minerals. A magnet touched to this sand will come up with its pole coated in black sand.

Credit: National Park Service.

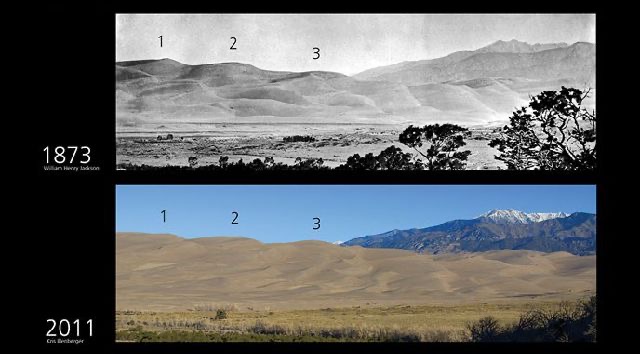

Looking at the sand-blasted interpretive panels that dot the trails on the edge of the dune field, one could be forgiven for imagining that the structure of the Dunes is ever-changing, shifting with the sands that built it—and yet this proves not been the case. The major features of the Dunes have been consistent for more than a century, and optically-stimulated luminescence tests—a measure that reports how recently a piece of quartz was exposed to sunlight—show that below the first few meters, much of the sand on the eastern side of the dune hasn’t seen the light of day in decades or centuries.

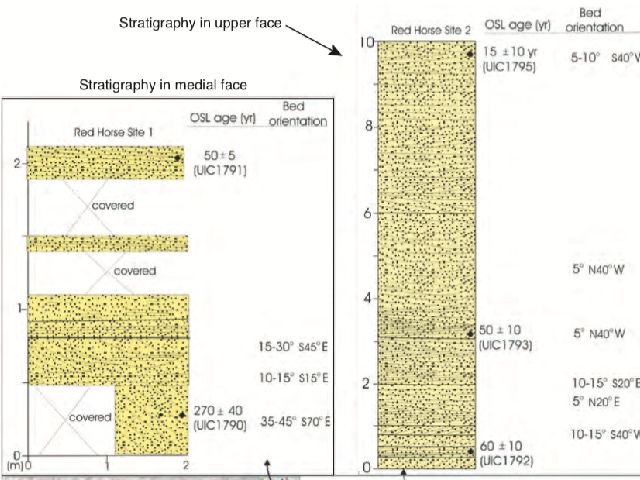

From the 2007 Rocky Mountain Section Friends of the Pleistocene Field Trip: Quaternary Geology of the San Luis Basin of Colorado and New Mexico, September 7–9, 2007, specifically Stop A2, “Optical Dating of Episodic Dune Movement at Great Sand Dunes National Park and Preserve” by Steve Forman.

All this while shorter parabolic dunes traveling from the swamps westward move several meters a year! The Great Sand Dunes seem to have found themselves in a state of dynamic equilibrium—winds and creeks sifting back and forth immense sheets of sand without upsetting the balance established between the forces; indeed, it seems likely that even a major human disturbance of the dunes would, in time, be re-shaped back into the old balance.

And yet a minor disturbance could kill them—at least, that is what the NPS, at the prompting of a concerned citizens group from the surrounding area, determined to be a likely outcome of a proposed project to extract the exceptionally pure waters running down the Sangre de Cristos for use elsewhere. A lowering of creek levels by just a few feet would halt the cycle holding the Great Dunes in place, allowing them to finally, inexorably beach themselves on the so-close mountains—and, for that matter, drain the water that suffuses many of the established dunes, supporting the structure of the Dunes as well as their idiosyncratic ecosystem.

A water-heavy region of the dune warped by the daily freeze-thaw cycle.

The dunes are criss-crossed by the distinctive tracks of the kangaroo rat, the sole mammal to make its life here in the Dunes—a place without drinkable water, where temperatures shift from freezing to unlivable daily. The temperatures it deals with in typical mammalian style, excavating extensive warrens in the sand beneath the few patches of grass that find purchase in the Dunes. There it can huddle through the highest and the lowest temperatures, intentionally collapsing the entrance to seal in a favorable climate. Water, meanwhile, is so tricky to find that the kangaroo rat simply doesn’t. All animals produce a small amount of water as part of their metabolic processes—recall the biological combustion reaction C6H12O6 + 6O2 -> 6H2O + 6CO2, where sugar and oxygen combine to produce energy, carbon dioxide, and water—and the kangaroo rat has adapted to survive on that metabolic water alone. It’s a life of short dashes from the warren to collect seeds in the short window between stark night and blazing sun, usually journeying less than a hundred meters from their home.

Even more exactly suited to the Dunes is the Great Sand Dunes Tiger Beetle, a species found only on the Great Sand Dunes and in the sand-plain to its west. A carnivore, the tiger beetle feeds on the insects, living or dead, that enter the Dunes, benefiting from how the extreme conditions of the region leave their prey more than usually vulnerable. Another burrower, the beetle here is likely holding itself against the sand in an attempt to warm up enough to take flight.

Despite his avid journaling, much about Zebulon Pike’s expedition is unclear, from minor details—did he cross the Sangre de Cristos at the Medano Pass or the Mosca?—to the very question of why he was sent on it at all. His superior General James Wilkinson acted without orders, and only retroactively received approval for his commissioning of the expedition. The consensus among historians is that Wilkinson was a collaborator in Aaron Burr’s illicit plans involving the Spanish territories—though no consensus exists as to what those plans were. Were Zebulon and his soldiers captured by the Spanish and held for months as a part of that plan? Or was Wilkinson simply that determined to learn the course of the Mississippi and the Arkansas, and then open relations with the Comanche?

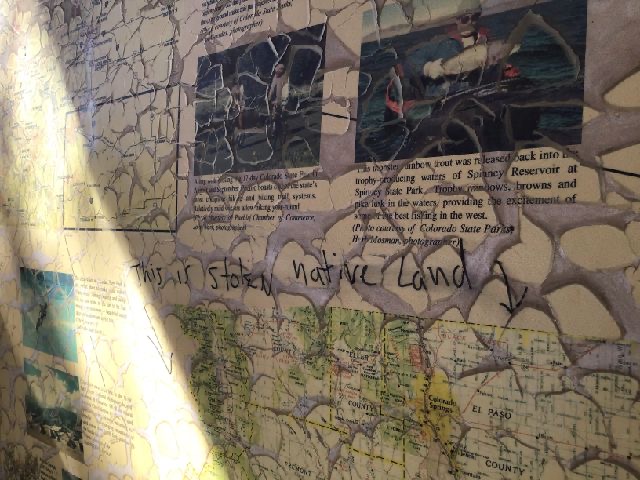

Take exit 74 on I-25, just north of the center of Colorado City, and drive west on the overpass. On your right will be the Cuerno Verde Rest Area. While not exactly spacious inside, the rest area offers several broad, shaded paths, a welcome respite from the cramped and road-boiled conditions inculcated by the Colorado highway system. You’ll have something to read, too: In a peculiar attempt to honor—or at least remember—Cuerno Verde, leader of a group of Comanches who warred with the occupying Spanish forces in the late 18th century, the Colorado Department of Transportation decided to commission a series of themed interpretive panels for the rest area—and that was where there trouble began. From Douglas Seefeldt’s “Constructing Comanche Pasts”:—

“The difficult year-and-a-half negotiation of the text and imagery to be depicted on these plaques can be seen as a lesson in how artistic license and history can conflict in the interpretation of the past. Nikolai’s initial draft of the "Cuerno Verde" marker text contained an account of the August 1779 battle between Governor Anza and the Comanche leader, a general description of Comanche lifestyle, and a biographical sketch of the rest area's namesake. This text made reference to "Chief" Greenhorn's "monstrous headdress;" it related Anza’s characterization of him as "the cruel scourge of this Kingdom," and pronounced Cuerno Verde as "the most notorious Comanche raider of his time." This passage, and the rude sketch of Cuerno Verde and his infamous helmet that accompanied it, combined to present little more than the kind of stereotypical violent "savage" figure that bedevils much of popular Indian history.”

(Note that “green horn” is a literal translation of “cuerno verde,” not referring to inexperience but to the literal green horn Cuerno Verde wore into battle.)

“;The minutes for this meeting suggest that although the drafts of all the marker texts were too long and some contained factual and stylistic errors, CDOT and CHS [Colorado Historical Society] representatives concluded that "the text was good and didn't require much editing."”

“In hindsight, it is clear that as the list of constituents in the creation of public memory at the Cuerno Verde Rest Area continued to grow, the questions over the interpretive markers escalated and the debate only became more contentious. The second interpretive marker review meeting between the design team and the CHS representatives in early June 1994 was, according to one disgruntled participant, "a marathon meeting of over three hours" that left both sides frustrated.“

Credit to Seefeldt.

“While the restrooms and landscaping were completed and opened to the public at the 1 September 1995 dedication ceremony, the historical content was conspicuously absent for some time.”

“In fact, given that Edward Tahhahwah’s recommendations did not result in any changes to the Cuerno Verde marker text or image, Comanches only significant participation in the project was at the dedication ceremony.”

“Wallace Coffey believed that "the local community had some spiritual significance to that territory," he admitted that he was initially "amazed that Colorado was willing to look at something like this—naming their new rest area for a Comanche historical figure. He was quite aware of the educational opportunities the honor of naming the rest area for a Comanche historical figure presented to the Comanche Nation. It is unfortunate, he said, "That we have to use a coat and tie in today's modern world, and that's our weapons of today. So from that proclamation you can tell that education is the new weapon. And it's different from the bow and arrow, what he [Cuerno Verde] had, but it's still utilized in a way that can bring an element of pride." The naming of the facility, Coffey believed, was a "tribute to the culture of our people.”

Cuerno Verde and many of his companions died while attempting to repel a 1779 “punitive expedition” led by Juan Bautista de Anza II, then the governor of Nuevo México. De Anza's return to Santa Fe almost certainly brought him past the Dunes, but neither he nor any of the 800 men comprising his army recorded their impressions of the place. Anza would live another decade before his 1788 death to apparently natural causes in Arizpe. His name is remembered up and down the West Coast for establishing the presidios—fortified garrison-towns—that would one day become California’s metropoli.

Pike would die only six years after his release from Spanish captivity, across the continent, fighting to seize the shore of Lake Ontario.

Lakes, rivers, highways.

A product of the same tectonic unease that built the San Luis Valley and the Sangre de Cristos, Huerfano or “Orphan” Butte is an isolated structure protruding out of the steady Colorado plain dozens of miles from the nearest mountain. A lonely intrusion of magma into what was once bedrock; now the weak sandstone bedrock has eroded away and it alone remains.