Issue №3: In the Valley

by W.L.

——

The mountains of southeast Vermont aren't tall, but they are numerous and densely-packed, typically ridge-y in character--the crests of the waves folded into the underlying crust of the area 400 million years ago. They run largely north-south, orthogonal to the overall west-east tilt of the land, making it hard to predict where water will pool and where it will run. Just two weeks ago, though, the task of searching out marshes and vernal ponds became easy to do by ear--the wood frogs had emerged, and they were busy.

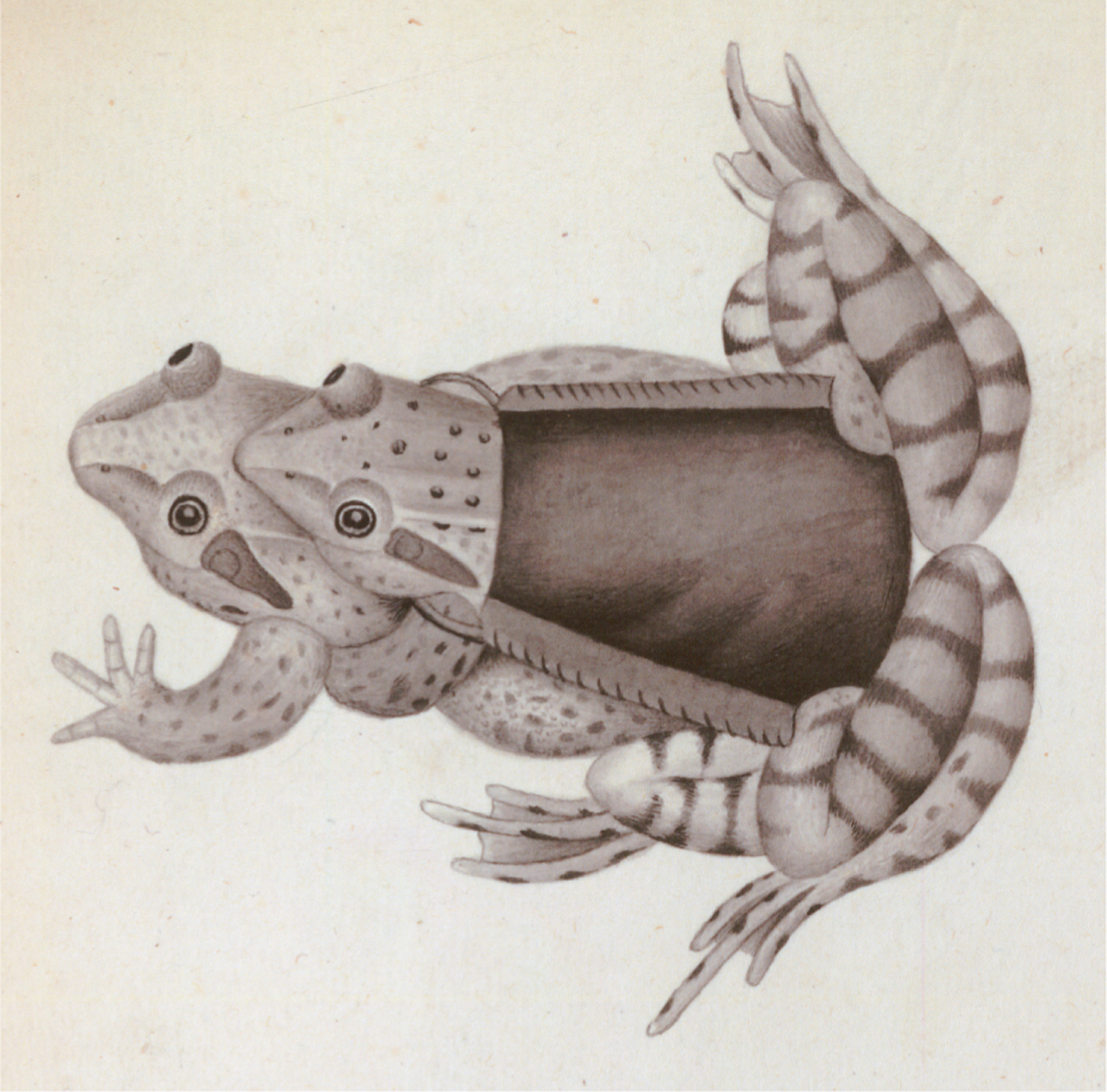

Wood frogs are good at handling cold temperatures--famously capable of freezing near-solid--and perhaps it's appropriate that they've evolved a similarly error-tolerant mating strategy. The males will grab onto anything wood-frog-shaped, including each other, different species of frog, and conveniently-sized sticks and rocks. A combination of competition and mistaken identity leads to the sort of multi-frog pileup pictured above. And yet, it works.

Wood frogs are good at handling cold temperatures--famously capable of freezing near-solid--and perhaps it's appropriate that they've evolved a similarly error-tolerant mating strategy. The males will grab onto anything wood-frog-shaped, including each other, different species of frog, and conveniently-sized sticks and rocks. A combination of competition and mistaken identity leads to the sort of multi-frog pileup pictured above. And yet, it works.

Frog spawn immediately draws the eye when walking past a vernal pond, but capturing the boluses of eggs with a camera can be tricky. The eggs must be submerged to remain viable, so the glassy surface of these still ponds acts as a mirror to the surrounding woods--a particular problem when wood frogs are spawning early in the season, before the leaves have come back in. The best hope, I find, is a day with clear skies. The light is stronger, but unlike cloud-scattered light has a relatively consistent polarization, and so much of the reflected light can be removed with a polarized lens--in my case, an LCD screen that I pulled out of a broken guitar tuner.

A week later, the high, clear song of the spring peeper marks vernal ponds from an even greater distance, their loud call carrying hundreds of feet. The other species of amphibian are rousing--including ones like this female green frog.

But they can't stay roused yet--the temperature hung around 35 degrees on the cloudy morning I saw this frog. Doubtless it would have leapt away on a warmer day before my lens was within an inch of its face. Instead it stayed put, sitting on its cool, wet rock as I left to travel downstream.

But they can't stay roused yet--the temperature hung around 35 degrees on the cloudy morning I saw this frog. Doubtless it would have leapt away on a warmer day before my lens was within an inch of its face. Instead it stayed put, sitting on its cool, wet rock as I left to travel downstream.

The mountains end where Mesozoic rifting tore them apart--the Connecticut River Valley. The peepers here call louder and earlier than their relatives in the hills, gifted as they are with moderate valley temperatures and the sodden, flat soil left by years of flooding and farming that yields broad, still pools heating under a newly-powerful April sun. These floodplains are the old lake-beds of Lake Hitchcock--the last beds to be drained as the once-immense lake left by the retreat of the Laurentide ice sheet diminished into the section of the modern Connecticut River between northeastern Vermont and mid-Connecticut (the state).

The mountains end where Mesozoic rifting tore them apart--the Connecticut River Valley. The peepers here call louder and earlier than their relatives in the hills, gifted as they are with moderate valley temperatures and the sodden, flat soil left by years of flooding and farming that yields broad, still pools heating under a newly-powerful April sun. These floodplains are the old lake-beds of Lake Hitchcock--the last beds to be drained as the once-immense lake left by the retreat of the Laurentide ice sheet diminished into the section of the modern Connecticut River between northeastern Vermont and mid-Connecticut (the state).

In addition to providing a home for the peepers, the farmers who tilled these fields surfaced some of the clearest evidence of glacial action you could hope for--fragments of the igneous mountain five miles to the north, the sole igneous mountain for almost a hundred miles in any direction. The stone walls here are near to wholly composed of these syenite (quartz-poor granite) rocks, pulled from the fields as they were being cleared for planting--rocks deposited below a thin layer of lake-bed sediment that quickly rose to near the surface over years of Vermont winters.

Ascutney, the igneous mountain, owes its existence to the same rifting event that built the valley. This particular stone in the wall is from near where the magma intruded into the surrounding ridge and wave of the area, as we can see from the captured fragment of "country" rock being assimilated into the magma.

Ascutney, the igneous mountain, owes its existence to the same rifting event that built the valley. This particular stone in the wall is from near where the magma intruded into the surrounding ridge and wave of the area, as we can see from the captured fragment of "country" rock being assimilated into the magma.

"For this reason the Dutch country boors, with great propriety, tho' in their vulgar way, call this manner of copulation, the riding season of the Frogs, as the male is carried about, riding, as it were, by the female." -- Jan Swammerdam, Bybel der natur.

Histories of Scientific Observation (ed. Daston and Lunbeck) is an anthology of essays on the forms observation took in discovery and research, as opposed to a more classical sense of science as a series of experiments. It can be a bit dry or over-concerned with technical points--it is, after all, an academic work, and the precise translation of "pants" being used in Italian is almost certainly going be relevant to someone who ends up citing it, as will sussing out the specific flavor of Freud any particular researcher subscribed to--but the variety and charming novelty of the episodes the essays study ensure the reader quickly forgets those digressions. My favorite of these covers Réaumur--yes, the thermometer guy--and his contemporaries as they investigate how frogs reproduce. Many a kid today can, and eagerly will, tell you how frog or fish eggs are fertilized--perhaps more, even, than can tell you how the process proceeds in mammals--but verifying that knowledge proved tasking to the aristocrat-scientist."I will put pants made of bladder on a male frog."

——