Issue №8: Oil is a form of waiting

by W.L.

Driving West — Galway Kinnell, When One Has Lived a Long Time Alone

A tractor-trailer carrying two dozen crushed automobiles overtakes a tractor-trailer carrying a dozen new.

Oil is a form of waiting.

The internal combustion engine converts the stasis of millennia into motion.

Cars howl on rain-wetted roads.

Airplanes rise through the downpour and throw us through the blue sky.

The idea of airplanes subverts earthly life.

Computers can deliver nuclear explosions to precisely anywhere on earth.

A lightning bolt is made entirely of error.

Erratic Mercurys and errant Cavaliers roam the highways,

A girl puts her head on a boy’s shoulder; they are driving west.

The windshield wipers wipe, homesickness one way, wanderlust the other, back and forth.

This happened to your father and to you, Galway — sick to stay, longing to come up against the ends of the earth, and climb over.

I had, the night before, as I sat on a bench outside the library reading on my phone, heard the sirens start up, the fire trucks and ambulances speeding up from their sheds a mile down the road, and saw them fly past the thin alley I sat in, passing in the moment it took for a single flash of their warning-lights to reveal the brick walls to either side of me-first a brilliant earthy light for the fire trucks, then the brilliant darkness of blue light on red brick. I could hear them heading off to the west, down Route 11 and into the sound-catching hills, as my eyes re-adjusted to streetlights, the illuminated,incorrect clock on the insurance building, the pizza parlor’s neon, the placid stars above the alley.

This was pretty normal.

It felt strange the next day to find, the next day, the burned-out hulk of a small truck just before the gate to a class-four unimproved road—a road the town shuts down for spring, to keep it from being worn down even faster during mud season—to smell the char of petroleum and plastic, see bits of white dust floating in the air, and feel, when the breeze hit just the right angle, the last breaths of the heat suffused into the frame as it burned. Of course, this was not strange—why else does the fire department get activated every other night, besides that the defining building-block of the twentieth and twenty-first centuries was oil? Hydrocarbons make themselves useful because they are more stable in pieces than they are together; when every adult in a country has a car, they will burn as surely as Sisyphus’ boulder will find its way downhill.

Still, even the statistically-inevitable wrecking of cars on the most disused roads was strange to me. And it had,wrecked on the road. A deep groove in the dirt and gravel started—or stopped—at the car and stretched far back down the already much-abused dirt road. So, I followed it along the way.

From time to time I could see the tread of large, knobbly tires digging into the mud of the road’s long-standing ruts, the tracks of whatever immense emergency vehicle has pulled the twisted frame of the thing back to the main roads. All along the way, the wreck scoured rocks from the road, leaving the surface pitted—

and split—

revealing the internal structure of many of these already-weathered rocks, rocks themselves revealed long ago by a far-larger scourer.

A mile up the road, past a streambed, a pond, and stretches of blackberries, it becomes a field of loose, burnt parts and oily puddles. Even a mechanic—which I certainly am not—would have trouble, I think, identifying the original provenance of many of the pieces here, appearing to my eye as nothing more than twisted bits of steel and bursts of unwound wire.

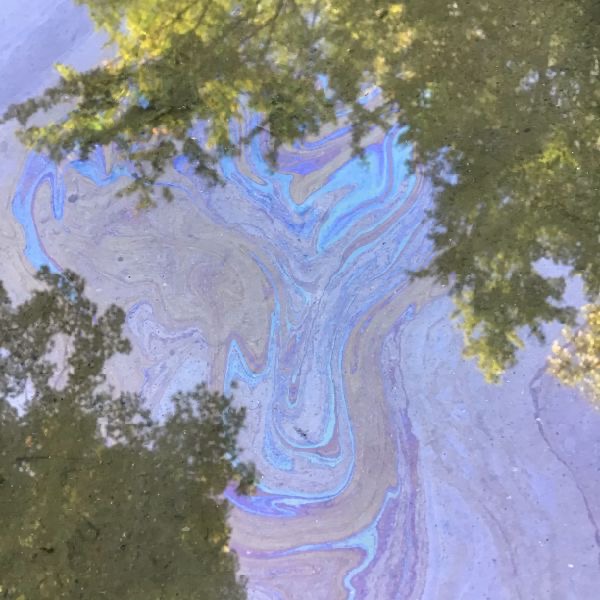

A patch of oil infiltrating the puddles and streams that cross this road.

Soem sort of specialized automotive batteries?

The alternator?

Melted automotive glass.

I legitimately have no idea.

These parts increase in frequency until—the site of the burn. The rough shadow of a truck is here, painted on the ground in carbon and re-congealed metal.

Nickel, maybe?—bb

Luckily, our August has been a wet one—each day seems to bring a new band of thunderstorms—so the fire did not spread. Instead, only a few dangling branches and adventurous blackberry stalks were caught, seemingly more by heat than by flame.

Collusion of Elements — Galway Kinnell, When One Has Spent a Long Time Alone

On the riverbank Narcissus poeticusholds an ear trumpet toward the canoe apparitioning past.

Cosmos sulphureous flings back all its eyelashes and stares.

The canoe enacts the Archimedean collusion of elements: no matter how much weight you try to sink it with, the water as vigorously holds it up.

Up to a point.

Likewise, the more pressure the fuel exerts on the O-rings, the more securely they fit into their grooves and keep the fuel from escaping.

At certain temperatures.

Pain is inherently lonely.

Of all the varieties of pain, loneliness may be the most lonely.

The Queen Charlotte Islanders used the method of fire to hollow a canoe out of a single log.

If there are burn-throughs, the vessel could founder; if cold O-rings, blow up.

As for you, Galway, the more dire the burn-throughs, the looser the O-rings, the greater the chance you could float or fly.

The car burned only about a half-mile from the summit of this hill-mountain—perhaps it was injured trying to drive around the obstacles placed by the summit’s owner, who allows hikers and hunters to cross the woods but bars trucks from using his logging roads.

The quickest way to the unimproved road from the center of town is by Route 11—by car. By foot, one instead takes a road so unsuited to the automobile that is not designated “unimproved” or “class four” but rather a “legal trail,” a legacy of a far different era for the town’s public works. Over time, the runoff of the hills has begun to turn this trail into a stream—in the spring, buckets of water run down its ruts; in winter, the whole trail is an ice slick, an act of reclamation that ironically seems to have preserved the trail more than erased it: once it dries out in May, the past year’s of worth of low underbrush growth has once again been swept from the path, leaving it clearer than the surrounding forest. The water, though, has dug chassis-ruining channels into the ground—and has done little about the trees that have fallen into the path.

Fortunate, that, for the red efts, who cross through this trail on wet, dim summer mornings, well-fed on terrestrial invertebrates and able to floppily—but quickly—run from anyone who would attempt to take their picture.